Causal Tree

Published:

This blog post is my reading notes of the paper Recursive partitioning for heterogeneous causal effects by Susan Athey and Guido Imbens.

1.Introduction

The paper “Recursive Partitioning for Heterogeneous Causal Effects” proposes the causal tree method for estimating heterogeneous causal effects. This method builds on regression tree and use the goodness of fit in treatment effects as tree splitting criterion. It is an “honest” approach, which means one sample is used to construct the partition and another to estimate treatment effects for each subpopulation. This method can work in high dimension covariates settings without sparsity assumptions.

There are two main challenges in this method.

First, in the two-staged partition finding and hypothesis testing procedure, many existing machine learning methods cannot be used directly for constructing confidence intervals. This is because those methods use the same data for model selection and model parameter estimation (“adaptive”). In some contexts, sparsity condition guarantees the consistency and asymptotic normality. The honest causal tree method does not use the same information for selecting the model structure (the partition of the covariate space) as for estimation given a model structure. This scheme can eliminate bias and have asymptotic properties at the cost of variance increasing due to sample splitting.

Second, traditional regression trees performing cross-validation based on the “ground truth”. However, the “fundamental problem of causal inference” is that the causal effect is not observed for any individual unit and so we do not directly have a ground truth. To address the issue, this paper constructs an unbiased estimate of the MSE of the treatment effect.

2.Problem setups

The observational data has the form $(X_i,Y_i,W_i)$, where $X_i$ is the feature vector of unit $i$ and could be high dimensional, $Y_i$ is the one dimensional realized outcome, $W_i\in{0,1}$ is the binary indicator for the treatment. Every unit has a pair of potential outcomes $(Y_i(0),Y_i(1))$.

\[Y_{i}^{\mathrm{obs}}=Y_{i}\left(W_{i}\right)= \begin{cases} Y_{i}(0) & \text { if } W_{i}=0, \\ Y_{i}(1) & \text { if } W_{i}=1. \end{cases}\]The unit-level causal effect is $\tau_i=Y_i(1)-Y_i(0)$, and the conditional average treatment effect is defined by

\[\tau(x) := \mathbb{E}[Y_{i}(1)-Y_{i}(0) \mid X_{i}=x].\]The original method requires that the observations are exchangeable and there is no interference, i.e. complete randomization. In this case the treatment probability for all values of $x$ is a constant. Usually the assumption is violated in observational study and the conditional treatment probability (“propsensity score”) $e(x):=P(W_i=1\mid X_i=x)$ is not a constant function.

Actually, the complete randomization assumption

\[\newcommand{\ci}{\perp\kern-1.3ex\perp} W_{i} {\perp\kern-1.3ex\perp}\left(Y_{i}(0), Y_{i}(1), X_{i}\right),\]can be relaxed to unconfoundness assumption

\[W_{i} {\perp\kern-1.3ex\perp}\left(Y_{i}(0), Y_{i}(1)\right) \mid X_{i}.\]The paper describe the causal tree method under the stronger complete randomization assumption, and the weaker unconfoundness assumption can be handled by inverse probability weighting.

3.Honest inference

A tree is a partition of the feature space $\mathbb{X}$.

\[\Pi=\left\{\ell_{1}, \ldots, \ell_{\#(\Pi)}\right\}, \text { with } \quad \cup_{j=1}^{\#(\Pi)} \ell_{j}=\mathbb{X} .\]Every value $x\in\mathbb{X}$ lies in one element of the partition, denoted by $\ell(x;\Pi)$. The tree estimator approximate the CATE $\tau(x)=\mu(1,x)-\mu(0,x)$ with a piecewise function:

\[\tau(x ; \Pi) := \mathbb{E}\left[Y_{i}(1)-Y_{i}(0) \mid X_{i} \in \ell(x ; \Pi)\right]=\mu(1, x ; \Pi)-\mu(0, x ; \Pi),\]which is a constant on each element of the partition. We usually have disjoint training dataset and testing dataset for machine learning tasks to relieve overfitting. The honest approach further split the training dataset into 2 parts, one part $\mathcal{S}^{\text {tr}}$ for estimating the tree and the other part $\mathcal{S}^{\text {est}}$ for estimating the conditional outcome or treatment effect. This procedure decouple the information from data in tree construction and target estimation.

Given a dataset $\mathcal{S}$, the outcome and CATE approximation at $x$ with the fixed partition $\Pi$ can be estimated by

\[\begin{gathered} \hat{\mu}(w, x ; \mathcal{S}, \Pi):= \frac{1}{\#\left(\left\{i \in \mathcal{S}_{w}: X_{i} \in \ell(x ; \Pi)\right\}\right)} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{S}_{w}: X_{i} \in \ell(x ; \Pi)} Y_{i}^{\mathrm{obs}}, \\ \hat{\tau}(x ; \mathcal{S}, \Pi) := \hat{\mu}(1, x ; \mathcal{S}, \Pi)-\hat{\mu}(0, x ; \mathcal{S}, \Pi) . \end{gathered}\]For a regression tree, every partition element (leaf) has a score, and the total score function is the sum of all scores on leaves subtracting the complexity penalty $\alpha\vert\Pi\vert$. The objective is to find the tree with the highest score by recursive partitioning. Here, the causal tree method use the modified minus mean square error (-MSE) as the score. The MSE evaluated on test dataset is

\[\operatorname{MSE}_{\tau}\left(\mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}, \mathcal{S}^{\text {est }}, \Pi\right)= \frac{1}{\#\left(\mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}\right)} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}}\left(\tau_{i}-\hat{\tau}\left(X_{i} ; \mathcal{S}^{\text {est }}, \Pi\right)\right)^{2}.\]However, the ground truth $\tau_i$ is unknown. The modification can handle this issue by subtracting $\tau_i^2$ in MSE, i.e.,

\[\operatorname{MSE}_{\tau}\left(\mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}, \mathcal{S}^{\text {est }}, \Pi\right):= \frac{1}{\#\left(\mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}\right)} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{S}^{\text {te }}}\left\{\left(\tau_{i}-\hat{\tau}\left(X_{i} ; \mathcal{S}^{\text {est }}, \Pi\right)\right)^{2}-\tau_{i}^{2}\right\}.\]This “subtracting unknown true value” trick was also used in the error analysis of nonparametric density estimation.

Then the final score is constructed by the expected MSE and penalty, which gives the honest criterion tobe maximized.

\[Q^H(\Pi):=-\operatorname{EMSE}_{\tau}(\Pi) - \alpha|\Pi|= \mathbb{E}_{\mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{te}}, \mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{est}}}\left[-\operatorname{MSE}_{\tau}\left(\mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{te}}, \mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{est}}, \Pi\right)\right]- \alpha|\Pi|\]The authors show that this modified minus EMSE has an unbiased estimator

\[\begin{gathered} -\widehat{\operatorname{EMSE}}_{\tau}\left(\mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{tr}}, N^{\mathrm{est}}, \Pi\right):= \frac{1}{N^{\mathrm{tr}}} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{tr}}} \left(\hat{\tau}\left(X_{i} ; \mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{tr}}, \Pi\right)\right)^2 \\ -\left(\frac{1}{N^{\mathrm{tr}}}+\frac{1}{N^{\mathrm{est}}}\right) \cdot \sum_{\ell \in \Pi}\left(\frac{S_{\mathcal{S}_{\mathrm{treat}}^{\mathrm{tr}}}^{2}(\ell)}{p}+\frac{S_{\mathcal{S}_{\mathrm{control}}^{\mathrm{tr}}}^{2}(l)}{1-p}\right) . \end{gathered}\]where $\hat{\tau}$ is obtained from $\mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{est}}$.

4.Cross validation?

TBD,…emm, I have not fully understood how the cross validation is incorporated in the honest inference.

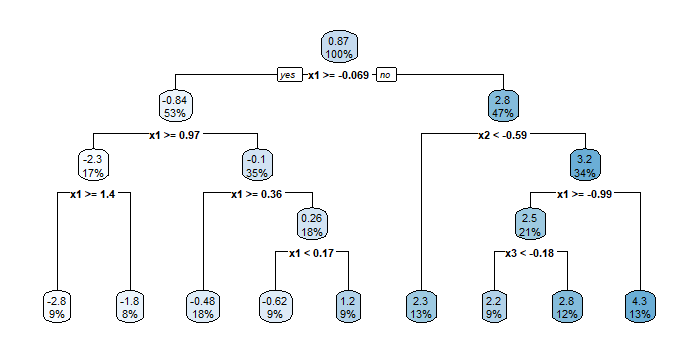

5.Example

To sum it up, the honest inference works as below (without cross validation version). The whole dataset is separated into training, estimating and testing dataset. For each fixed value of $\alpha$, we have an empirical version $\hat{Q}^H(\Pi)=-\widehat{\operatorname{EMSE}}_{\tau}\left(\mathcal{S}^{\mathrm{tr}}, N^{\mathrm{est}}, \Pi\right)-\alpha\vert\Pi\vert$ evaluated on the training and estimating dataset, which controls the growth of causal tree. After the tree is constructed, the testing MSE is computed based on testing dataset. The choice of penalty hyperparameter $\alpha$ and the best tree corresponds to the smallest testing MSE.

The paper consider a family of models in the simulation study. In all designs the marginal treatment probability is $P =0.5$, $K$ denotes the number of features. The mean effect is $\eta(x)$ and the treatment effect is $\kappa(x)$. For $w=0,1$, the potential outcomes are

\[Y_{i}(w)=\eta\left(X_{i}\right)+\frac{1}{2} \cdot(2 w-1) \cdot \kappa\left(X_{i}\right)+\epsilon_{i},\quad \epsilon_{i} \sim \mathcal{N}(0, .01),\ X_{i} \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1),\ X_i\ci \epsilon_i.\]The 2nd setup

\[K=10 ; \eta(x)=\frac{1}{2} \sum_{k=1}^{2} x_{k}+\sum_{k=3}^{6} x_{k} ; \kappa(x)=\sum_{k=1}^{2} 1\left\{x_{k}>0\right\} \cdot x_{k}\]is also the example named “simulation1” in the R package “causalTree”, which can be found on https://github.com/susanathey/causalTree. The package “causalTree” relies on the package “rpart” for recursive partitioning for classification, regression and survival trees.

library(causalTree)

tree <- causalTree(y~ x1 + x2 + x3 + x4, data = simulation.1, treatment = simulation.1$treatment,

split.Rule = "CT", cv.option = "CT", split.Honest = T, cv.Honest = T, split.Bucket = F,

xval = 5, cp = 0, minsize = 20, propensity = 0.5)

opcp <- tree$cptable[,1][which.min(tree$cptable[,4])]

opfit <- prune(tree, opcp)

rpart.plot(opfit)

In the “causalTree” function, “cp” is the complexity parameter; “minsize” is the minimal number of data in a leaf node, which helps controlling the variance; “propensity” equals to constant 0.5, meaning that all individuals has probability $0.5$ to get treatment. The documentation says that “Unit-specific propensity scores are not supported; however, the user may use inverse propensity scores as case weights if desired”. But I wonder how to do this in practice?

The “prune” is a generic and the corresponding method in “rpart” pacakge is “prune.rpart”. The usage prune(tree, cp) requires the fitted model object and the complexity parameter. See https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rpart/rpart.pdf.

References

https://www.cnblogs.com/gogoSandy/p/11711918.html https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/115223013