Covergence cross mapping

Published:

1.Background

Convergent Cross Mapping (CCM) is a method for establishing causality from long time series data (\(\geq 25\) observations). The method was first proposed in 1990 by Sugihara et al and revisited in 2012.

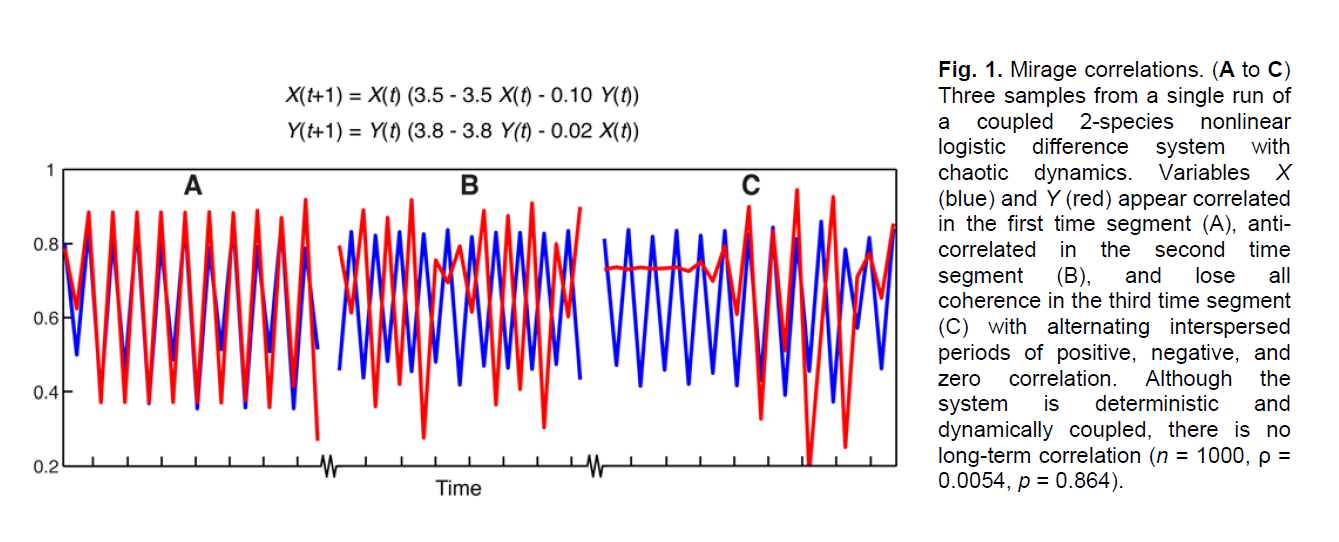

Identifying causality in complex systems can be difficult. For variables with causal relation(s), the behavior of their observations in a segment of times may depends on system state: positively coupled at some times , at other times unrelated or even negatively coupled. An example in the 2012 paper exactly illustrates the phenomenon.

Indeed, the paper consider nonlinear difference equations of this form:

\[\begin{aligned} &X(t+1)=X(t)\left[r_{x}-r_{x} X(t)-\beta_{x, y} Y(t)\right] \\ &Y(t+1)=Y(t)\left[r_{y}-r_{y} Y(t)-\beta_{y, x} X(t)\right] \end{aligned}\]As that in the example, the correlation exhibits different behavior for different system states, which seems useless in inference, not to mention correlation itself is not causation.

One approach to investigat causal linkages among time series variables is Granger causality (GC), which interpreter “causality” as the ability of prediction. Variable X is said to “Granger cause” Y if the predictability of Y (in some exact idealized model) declines when X is removed from the universe of all possible causative variables.

The key assumption of GC is separability, namely that, the causative factor is exogenous and not contained in past time series of the outcome variable. Separability is satisfied in most linear systems and pure stochastic systems. Besides, GC also works well in nonlinear systems with stable points or limit cycles, or with strongly-coupled variables.

However, GC does not perform well in general nonlinear systems, especially for those with weak of moderate coupling. Information about the causal factor are redundantly presented in the outcome variable time series (see section 2). That is, the causal factor can be removed in the equation system and the outcome variable can be predicted by its history, as well as with incorporating the causal factor. In this sense, GC will conclude that the causal factor is not the cause of the outcome variable, since there is no gain in predicability when adding the causal factor in the prediction model. Moreover, common external driving variables (confounders) can also make GC fail.

CCM is an alternative approach, not competing with the many effective methods that use GC, but rather aimed specifically for cases not covered by GC (non-separable nonlinear, weak coupling, confounders).

2.Idea

Consider a dynamic process $\phi$ in an $E$-dimensional state space, whose trajectories converge to a $d$-dimensional manifold $M$ such that \(\phi: M\mapsto M\) (\(\underline{m}(t+1)=\phi(\underline{m}(t))\in M\)). Let $X$ be a map from $M$ ro real numbers set \(\mathbb{R}\). Then the trajectory of points in $M$ maps to a time series ${X}={X(1),…X(L)}$ for each $X$. The length of the time segment (library size) is $L$.

Takens’s theorem ensures that, as long as the embedding dimension $E>2d$, a lagged-coordinate embedding time-lagged values of ${X}$ as coordinate axes can reconstruct a shadow attractor manifold $M_X$, consisting of the set of vectors \(\underline{x}(t)=\langle X(t), X(t-\tau),...,X(t-(E-1)\tau)\rangle\), where the time lag \(\tau\) is positive. Generically, points \(\underline{x}(t)\) on $M_X$ map 1:1 to points \(\underline{m}(t)\) on $M$ so that $M_X$ is a diffeomorphic (exists inversible smooth map) reconstruction of the original attractor manifold $M$.

In dynamical systems theory, time series variables (say $X$ and $Y$) are causally linked (or coupled?) if they are from the same dynamic system, thereby sharing a common attractor manifold $M$. According to the tme-lagged reconstruction, there are shadow manifolds $M_X$ and $M_Y$, both of which are diffeomorphic to the original attractor manifold $M$.

Convergent cross mapping (CCM) determines how well local neighborhoods on $M_X$ correspond to local neighborhoods on $M_Y$. The procedure is first to find the nearest neighbors of a point \(\underline{y}(t)\) in $M_Y$, and use their time indices to find the corresponding points in $M_X$. These points will be the nearest points to \(\underline{x}(t)\) only if the causation \(X\rightarrow Y\) exists. This approximation via two shadow manifolds is called “cross mapping”, and the word “convergent” indicates that the prediction error converges to 0 as the time lag length goes to infinity.

When the causal link is mutual, each variable can identify the state of the other. However, if the link is only unidirected, one variable $X$ is a stochastic environmental / external forcing driver of a population variable $Y$, information about the states of $X$ can be recovered from series of $Y$, but not vice versa. In this case, $M_Y$ is a valid manifold diffeomorphic to the original manifold $M$, but there is no 1:1 mapping between $M_X$ and $M$, because the exogenous variable $X$ contains no information about the dynamics of $Y$. Cross mapping of $Y$ using $M_X$ will not converge in the limit as $L$ approaches infinity.

The paper also illustrate the phenomenon with an simple example of the same form as (1). Consider the following 2-species logistic model, where the parameter \(\beta\) governs the sensitivity of $X$ to changes in $Y$.

\[\begin{aligned} X(t+1)=3.9 X(t)[1-X(t)-\beta Y(t)] \\ Y(t+1)=3.7 Y(t)[1-Y(t)-0.2 X(t)] \end{aligned}\]The equations can be written as

\[\begin{aligned} \beta Y(t)=1-X(t)-X(t+1) / 3.9 X(t) \\ 0.2 X(t)=1-Y(t)-Y(t+1) / 3.7 Y(t) \end{aligned}\]where $Y$ is represented by the time series of $X$ and vice versa. However, this is insufficient for recover the cross map dynamics since the right hand side requires future information. One need to plug (3) back into (2) and obtain

\[\begin{aligned} &X(t)=\frac{3.9}{0.2}\left\{(1-\beta Y(t-1))\left(1-Y(t-1)-\frac{Y(t)}{3.7 Y(t-1)}\right)-\frac{1}{0.2}\left(1-Y(t-1)-\frac{Y(t)}{3.7 Y(t-1)}\right)^{2}\right\} \\ &Y(t)=\frac{3.7}{\beta}\left\{(1-0.2 X(t-1))\left(1-X(t-1)-\frac{X(t)}{3.9 X(t-1)}\right)-\frac{1}{\beta}\left(1-X(t-1)-\frac{X(t)}{3.9 X(t-1)}\right)^{2}\right\} \end{aligned}\]As $\beta$ approaches 0, the cross map model of $X$ remains well behaved, but for $Y$ there is a singularity. Informally, when $\beta = 0$, $X$ moves through the state-space without regard to the current location of $Y$. Therefore the history of $X$ is irrelevant for determining $Y$.

This example provides another argument for why the convergence of cross-mapped estimates is a necessary condition for causality. (Suprisingly no counter example for insufficiency!) Moreover, even though $X$ and $Y$ are coupled, we can write an exact model for predicting $X$ ($Y$) on the basis of its past history alone. Notice that $Y$ ($X$) can be removed from the set of hypothetical causal variables without diminishing the predictability of $X$ ($Y$), the Granger Causality (GC) framework will conclude that no causal relations between $X$ and $Y$.

3.Algorithm

3.1 Basic version —— Let \(\{X\}=\{X(1), ..., X(L)\}\) and \(\{Y\}=\{Y(1), ..., Y(L)\}\) be two time series of length $L$. The lagged-coordinate vectors \(\underline{x}(t)=\langle X(t), X(t-\tau), ..., X(t-(E-1)\tau)\rangle\) for \(t\in [1+(E-1)\tau, L]\) reconstruct the shadow manifold $M_X$. The cross-mapped estimate \(Y(t)\mid M_X\) is computed by the following steps:

- Locate the contemporaneous lagged-coordinate vector \(\underline{x}(t)\) in $M_x$ and find its $E+1$ (the minimum number of points needed for a bounding simplex in an $E$-dimensional space) nearest neighbors

- Identify the time indices (from closest to farthest) of the $E+1$ nearest neighbors of \(\underline{x}(t)$: $t_1, ..., t_{E+1}\)

- Compute the weights based on the distance between \(\underline{x}(t)\) and its nearest neighbors: \(w_{i}=u_{i} / \sum_{j=1}^{E+1} u_{j} \quad i=1 \ldots E+1,\) where \(u_{i}=\exp \left\{-d(\underline{x}(t), \underline{x}\left(t_{\mathrm{i}}\right)) / d(\underline{x}(t), \underline{x}\left(t_{1}\right))\right\}\) and $d(\underline{x}(s), \underline{x}(t))$ is the Euclidean distance between two vectors.

- Compute the estimate \(\hat{Y}(t) \mid M_X=\sum_{i=1}^{E+1} w_{i} Y\left(t_{\mathrm{i}}\right)\)

The basic algorithm itself is simple once understanding the idea behind it. Maybe just the choice of exponential function as the transformation of distances is not very clear. One can implement the algorithm easily with basic libraries in programming languages like R or Python. Since it finds nearest neighbors for each time index in a sequence of approximate length $L$, if we don’t consider optimization tricks, the algorithm has time complexity $O(L^2)$.

If the causation $Y\rightarrow X$ exists, the nearest neighbors of $M_X$ should identify the time indices of corresponding nearest neighbors on $M_Y$. As the library length $L$ increases, the reconstructed discrete version attractor manifold gradually becomes denser and fills in the manifold. Hence the $E+1$ nearest neighbors converge to \(\underline{x}(t)\) and the estimate \(\hat{Y}(t) \mid M_X\) converges to $Y(t)$. The estimate precision (or correlation) increases to 1.

3.2 Extensions

tbd

References

Detecting Causality in Complex Ecosystems

Supplementary Materials for Detecting Causality in Complex Ecosystems

Journal club: Detecting causality in complex ecosystems